Oregon State Fair

Schroeder Law Offices will be working the Women for Agriculture booth at the Oregon State Fair on Friday, August 26th from 1:00 PM to 3:30 PM and Sunday, August 28th from 3:30 PM to 6:00 PM.

Schroeder Law Offices will be working the Women for Agriculture booth at the Oregon State Fair on Friday, August 26th from 1:00 PM to 3:30 PM and Sunday, August 28th from 3:30 PM to 6:00 PM.

Laura A. Schroeder is the founding partner of Schroeder Law Offices. Long respected in the water rights arena, Laura has generously shared her valuable experiences and provided some great advice. A few questions we asked Laura:

What motivated you to practice water law and start Schroeder Law Offices?

I used to work on a farm and did work related to irrigation. From that experience, I learned the importance of water. Also, my father was a lawyer and I got Influenced by him and became a lawyer. In my early practice years, I worked in a number of law firms and practiced in different areas of law. I then realized that my passion was in water law, so I started my practice.

What is your go-to productivity trick? How do you stay motivated?

The most important thing is that I really enjoy what I do, and I like the people I work with, so I always get motivated when I work. Also, I have the habit of mediation. Meditation helps me center myself.

What do you consider the most important thing about being a good lawyer?

I find the most important thing is to be proud of your profession. I dislike jokes about lawyers because that is disrespectful.

Where can I find you on the weekend?

I love spending time with my family! Last weekend I helped with cleaning at my son’s place, and the week before that I attended my niece’s wedding. I always consider family the most important thing. When I have free time, I also help with writing family genealogy.

What is one thing you like the most about working at Schroeder Law Office?

I like it because lawyering is an intellectually challenging job. In the legal profession, the challenge you need to face constantly changes, and you need to develop new strategies based on the new challenge. Also, at Schroeder Law Offices, everyone has different perspectives on solving problems. I enjoy discussing and developing new strategies with everyone.

Do you have some advice that you can give to young lawyers and law students who are interested in water law?

Beside law school, it is important to have real-life practice experiences as much as possible, because in the legal profession you need to work with people. When I started to practice, I did clerkship with the government, worked with my father, and worked in private law firms. I learned from that experience that working with different kinds of people and lawyers is essential, because it offers you an opportunity to learn from the people you interact with. If you just focus on just one thing, you will definitely miss out on other things.

[This article was originally published in the February, 2022 Oregon Real Estate and Land Use Digest by the Section on Real Estate and Land Use, Oregon State Bar]

In Oregon, water rights must be beneficially used according to their terms at least once every five years to remain in good standing. If they are not, water rights are subject to cancellation for forfeiture. ORS 540.610. Thus, Oregon’s forfeiture statute enacts the “use it or lose it” principle that is common in Prior Appropriation water system states. Water right holders must use their water rights or risk cancellation.

In the late 1980s, the Oregon State Legislature recognized instream beneficial uses for water, allowing the State to hold or lease water rights for instream purposes such as recreation, navigation, pollution abatement, and fish and wildlife. Under ORS 537.348, water right holders may temporarily lease water rights to the State for instream purposes for up to five years, renewing such instream leases thereafter. The statute provides that water rights leased instream are “considered a beneficial use.” ORS 537.348(2). As such, the forfeiture provisions of ORS 540.610 are not triggered during the period a water right holder leases their water right instream. Many water right holders use the instream lease program to safeguard their water rights in times when such water rights might not otherwise be used once every five years. The instream lease program serves dual purposes of providing instream flows while protecting private property interests in water use.

WaterWatch of Oregon v. Water Resources Department, 369 Or 71 (2021), questioned whether a hydroelectric water right could be leased instream and thereafter, once the lease(s) expired, be used again for hydroelectric or other beneficial uses of water. At issue in this case is a hydroelectric water right held by Warm Springs Hydro, LLC (“Warm Springs”). In 1995, Warm Springs’ predecessor shut down the associated hydroelectric project and began a series of instream leases from 1995 to 2020. WaterWatch of Oregon (“WaterWatch”) petitioned for judicial review of the Oregon Water Resources Department’s (“OWRD’s”) final order approving the 2015-2020 instream lease, and Warm Springs intervened.

In addition to the forfeiture provisions that are applicable to all water rights, ORS 543A.305 (enacted in 1997) applies specifically to hydroelectric water rights. The statute provides:

Five years after the use of water under a hydroelectric water right ceases, or upon expiration of a hydroelectric water right not otherwise extended or reauthorized, or at any time earlier with the written consent of the holder of the hydroelectric water right, up to the full amount of the water right associated with the hydroelectric project shall be converted to an in-stream water right, upon a finding by the Water Resources Director that the conversion will not result in injury to other existing water rights.

ORS 543A.305(3). Further, the statute specifies that the conversion to an instream water right “shall be maintained in perpetuity, in trust for the people of the State of Oregon.” ORS 543A.305(2).

Prior to this case, OWRD interpreted ORS 543A.305(3) similar to the forfeiture statute; that is, so long as a hydroelectric water right continues to be used for hydroelectric water use or another beneficial use under an instream lease, the hydroelectric water right is not subject to conversion to a permanent instream water right. WaterWatch challenged OWRD’s interpretation, arguing hydroelectric water rights are subject to conversion five years after the specific hydroelectric use of water ceases. The Marion County Circuit Court and the Oregon Court of Appeals both ruled in favor of OWRD and Warm Springs, but the Oregon Supreme Court reversed and remanded the decision on December 23, 2021.

The Oregon Supreme Court reviewed the text of the two statutes in conjunction with the context of the statutes and legislative history. The Court held “the use of water under a hydroelectric water right” means water use only for hydroelectric purposes as specified in the water right certificate, and does not include beneficial use under an instream lease. WaterWatch of Oregon, 369 Or at 88-89. The Court reasoned that once a hydroelectric water right is leased instream, the beneficial use is converted to another purpose other than hydroelectric water use. Id. at 91-94. The Court further held that “ceases” under the statute has an ordinary meaning, so Warm Springs’ water right was subject to conversion to an instream water right in the year 2000, five years after the hydroelectric project was shut down. Id. at 89-91.

The Oregon Supreme Court’s ruling will have significant impacts on hydroelectric water rights in the State. Most obviously, other hydroelectric water right holders in situations analogous to Warm Springs may face conversion of their hydroelectric water rights to permanent instream water rights. As such, property owners who believed they were appropriately safeguarding valuable water right holdings through instream leases may find themselves mistaken.

Another consequence of the Court’s decision is that instream leases over four years in length are essentially “off the table” for hydroelectric water rights. Hydroelectric water uses must resume within five years or risk conversion to permanent instream water rights. Thus, there is no incentive for hydroelectric water users to lease their water rights instream to avoid forfeiture, and, in the process, guarantee instream flows. Instead, the ruling incentivizes quick transfers to other, possibly more consumptive, water uses through the transfer process before the hydroelectric water right is converted to a permanent instream water right. ORS 543A.305(7).

Finally, conversion of appropriative water rights to instream water rights allows the State to enforce against upstream junior water users to ensure instream rights are satisfied. Conversion of large, early priority hydroelectric water rights to permanent instream purposes may have the outcome of increased regulation against other water right holders.

The original article is available in PDF format here.

(The below article is reproduced from the January, 2022 issue of Oregon Cattleman, the publication of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association. For a PDF copy of the article, use this link.)

2021 was a terrible water year in Oregon. We experienced record high temperatures and record low precipitation, after several years of already below-average precipitation, little or no carryover water in reservoirs, historically dry soils, and severe wildfires. This year highlighted the need for additional water storage to increase water security during times of drought.

At the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association’s annual meeting, the Water Resources Committee voted to adopt a resolution promoting water infrastructure and storage to guide the organization’s priorities going forward, and the Board adopted the resolution. This policy will be especially important in coming years, as we face increasing roadblocks to achieving water storage and infrastructure goals. State water policies are oftentimes conflicting, recognizing the importance of creating additional storage, while at the same time promoting activities that foreclose opportunities for storage.

For example, Oregon’s Integrated Water Resources Strategy includes a “recommended action” to plan and prepare for drought resiliency. The Strategy also includes a “recommended action” to develop instream water protections. These two strategies are not necessarily opposed, however, when one strategy is actively pursued while the other falls by the wayside, the State’s actions do not balance both needs. Moreover, only so much water exists within water basins, and the creation of instream water rights takes that water “off the table” for purposes of increasing or creating water storage.

In 1987, the Oregon State Legislature passed the Instream Water Right Act allowing the State to convert minimum perennial instream flows to instream water rights, apply for new instream water rights, and lease or transfer existing water rights to instream uses such as recreation, pollution abatement, and fish and wildlife. Thus, instream water rights are not a new concept. However, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (ODFW’s) website details that the agency “re-established” its instream water rights filing program in 2016, “consistent with Oregon’s Integrated Water Resources Strategy.” Thus, we have seen in the last few years hundreds of applications for instream water rights filed by ODFW in different water basins throughout the State. ODFW’s policy stated in its administrative regulations is “to obtain an in-stream water right on every waterway exhibiting fish and wildlife values.” OAR 635-400-0005.

Unlike appropriative water rights, instream water rights are not constrained by the amount of water actually available to fulfill the instream water right. Rather, ODFW’s applications may request the amount of water ODFW determines is needed to support the fish and/or wildlife species. As such, ODFW applications regularly include requested rates that exceed available stream flows. Such applications, if approved, have the effect of precluding any new appropriative water use rights within or upstream from the stream reach designated in the application.

Moreover, once instream water rights are in place, existing water right holders lose the flexibility to transfer their points of diversion upstream. The instream water right holder (the State) must consent to the “injury” the transfer would cause. In exchange for its consent, the State typically requires mitigation by placing a portion of the transferred water rights instream. The 1987 Instream Water Right Act provided, “The establishment of an in-stream water right…shall not take away or impair any permitted, certificated or decreed right to any waters or to use of any waters vested prior to the date the in-stream water right is established…” ORS 537.334(2). In practice, however, existing water right holders lose the flexibility they might have otherwise enjoyed to modify their water rights as needed for their operations.

This is not to say that instream water rights have no place or value. The reason for outlining the increased emphasis on instream rights recently, and the effects such rights have on new and existing appropriative water rights, is to point out that we, as a State, are falling short on drought resiliency preparation efforts at the same time water resources are being irreversibly committed to instream purposes. In 2013, when the Legislature passed Senate Bill 839, establishing the Water Supply Development Fund, many hoped that the fund would be used to increase water storage throughout the State. As a whole, that fund has not created substantial new storage. The State must do better to carry forward all components of the Integrated Water Resources Strategy, including planning and preparation for drought resiliency through water storage and infrastructure improvements.

The Oregon Water Resources Department (OWRD) received a large funding package in the 2021 regular session of the Legislature. The Oregon Cattlemen’s Association joined a coalition letter to OWRD outlining recommended priorities for implementing that funding. The first priority in that letter is a request that OWRD renew its focus on increasing storage and improving disaster resiliency. Congress recently passed the Infrastructure Investment Jobs Act, and the letter further asks OWRD to develop a plan to leverage federal funds in support of these efforts.

In addition to government reprioritization and implementation of plans to prepare for droughts, individuals and groups from the agriculture community will need to lead the way and identify projects in their communities. It is possible that storage opportunities may be identified through place-based planning efforts in partnership with State agencies. Soil and water conservation districts and other local entities can also assist individuals to navigate the myriad of questions and processes involved. The Oregon Cattlemen’s Association will continue to advocate for legislation and government actions in furtherance of this goal, and assist members who are interested in exploring new or expanded water storage opportunities.

If you are interested, you might also check out Schroeder Law Offices’ free webinar about winter storage, available at: http://water-law.com/water-right-video-handbook-guide/.

Winter storage for use throughout the year may still be a viable option with surface water and hydrologically connected groundwater oftentimes unavailable for new permitting. It could be more important than ever during periods of prolonged drought!

Winter storage for use throughout the year may still be a viable option with surface water and hydrologically connected groundwater oftentimes unavailable for new permitting. It could be more important than ever during periods of prolonged drought!

Laura Schroeder and Sarah Liljefelt will present a free, hour-long webinar on Tuesday, August 3rd, from noon to 1:00 PM, Pacific Time.

In this webinar you will learn about the roadblocks to developing surface water and hydraulically connected groundwater, and how to determine if water is available for winter storage. Then we will address the dual permitting process, how to optimize the storage location, and obtaining necessary flood easements. Finally, we will discuss what is involved in sharing storage by contractual arrangement.

There will be live Q&A. Questions will also be accepted in advance from registrants by email to Brittany Jesek b.jesek@water-law.com

Please register in advance for the new webinar at https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/2616261961273/WN_CNx3ZdMBRf62SXFmD80EMw

We will then send you a link to the actual webinar.

This new topic is the fourth of our “VACCINE” webinar series. It follows upon last spring’s popular “COVID” webinar series. You can view recordings of our prior webinars at Water Right Video Handbook or Guide.

Also, stay tuned for additional upcoming topics:

We look forward to having you with us next Tuesday!

In the second installment of the VACCINE webinar series, Schroeder Law Office presents “What to Do When There is No Water: Drought Tools Explained.” This webinar took place on Tuesday, June 22, 2021, from noon to 1:00 PM, Pacific time. A recording is now posted.

In the second installment of the VACCINE webinar series, Schroeder Law Office presents “What to Do When There is No Water: Drought Tools Explained.” This webinar took place on Tuesday, June 22, 2021, from noon to 1:00 PM, Pacific time. A recording is now posted.

Laura Schroeder and Caitlin Skulan will discuss drought tools in Oregon, Nevada, and Idaho. The discussion will include the requirements for a declaration of drought in each jurisdiction, tools available to water managers and users during drought, and priorities of use during water shortages.

Can’t make it on June 22nd? Afterwards, webinars are available here. Schroeder Law Offices gives you free “on demand” access to educational content while maintaining social distance! Also check out our “Where is the Water?” articles in the WaterSPOT (Nevada) and the upcoming issues of the Water Gram (Idaho), and H2Oregon.

Stay tuned to the Schroeder Law Offices blog for announcements about the upcoming webinars. The third installment of the VACCINE series, “What Terms to Include in a Well Share Agreement” was presented Tuesday, July 13, 2021. You can find a recording of that webinar here.

If you have any issues viewing, please contact Scott Borison at scott@water-law.com.

(Image credit: https://www.cnbc.com/2014/09/16/droughts-predictions-are-difficult-on-when-theyll-end.html; https://www.kunr.org/post/drought-fires-and-heat-look-nevadas-climate-earth-day-2021#stream/0)

Unappropriated water has long been considered a public resource. It is subject to private ownership rights and development, to be sure. But the law generally treats water differently compared to commodities like consumer goods or other natural resources like lumber. The UN recognized water’s essential role in the public commons in Resolution 64/292. It declared a “human right to water” and acknowledged “clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights.” However, recent developments in water markets could signal a shift in long-held perspectives. In early December, California water futures contracts began trading on stock exchanges for the first time ever, bringing water in line with other commodities like gold and oil.

At its most basic level, a futures contract is an agreement to buy or sell a commodity at a future date. The price and amount is set at the time of the contract. This gives cost certainty to buyers in volatile markets, but also invites outside speculation. The water futures here are tied to the Nasdaq Veles California Water Index, which tracks the spot market for water in California. The index has doubled in value over the past year. Tying futures contracts to the index allows buyers to “lock in” a price long before they will actually purchase water.

Proponents of the venture claim that the futures will add price certainty and transparency to the traditional spot water markets. Spot markets typically bring high prices and uncertainty for water users in dry times. Farmers, municipalities, manufacturers, and energy producers can look to the futures market for data on current and past prices. They can use that information to make informed decisions about what future prices might look like in dry times down the road. This allows water users to enter into futures contracts to offset the higher cost of water in the future.

However, some detractors fear placing water futures on the open market undermines water’s value as a basic human right. Pedro Arrojo-Agudo, a UN expert on water, worries that the futures market poses a risk to individual water users. This is because “large agricultural and industrial players and large-scale utilities are the ones who can buy, marginalizing and impacting the vulnerable sector of the economy such as small-scale farmers.” Additionally, trading futures on stock exchanges invites speculation from outside investors like hedge funds and banks. Speculation could lead to bubbles like we saw in 2008 with the housing and food markets. After all, western states that regulate water under the Prior Appropriation Doctrine prohibit water speculation. This fear may be far from realization, though. Analysts believe that water is currently too abundant worldwide to become a highly sought after commodity on global financial markets.

Though brand new, California’s water futures trading represents an interesting experiment in water market innovation. Currently, spot water markets are the dominant avenue to buy and sell water. Some entities, like the Western Water Market, are trying to make the process easier. These futures are another step in that direction. In Schroeder Law Office’s webinar, “Buying and Selling Water Rights,” we noted the difficulties in developing water markets. For example, water isn’t fungible, water rights include specific conditions and restrictions, and the transfer process is often lengthy, limited in allowable scope, and expensive. On top of that, scarcity issues abound. Although the new water futures trading will not solve those particular problems, it is worth keeping an eye on. Water futures may successfully help California water users better manage prices. If so, futures trading could spread throughout other western states.

Stay tuned to Schroeder Law Offices’ Water Law Blog for more water news!

This blog was drafted with assistance from law clerk Drew Hancherick, a student at Lewis & Clark Law School.

Nevada Division of Water Resources (“NDWR”) has drafted proposed water related regulations and the public is encouraged to get involved by attending the upcoming workshops. The draft regulations concerning water use are R169-20 (concerning extensions of time) and R170-20 (concerning Water Right Surveyor licenses).

R169-20

This draft regulation proposes, among other things, to include new definitions such as defining “beneficial use,” “perfecting an appropriation” and “steady application of effort.” The proposed regulation also adds additional requirements necessary on an Application of Extension of Time to file a proof of completion and/or proof of beneficial use. The proposal provides guidelines for evidence the State Engineer can consider in determining if the applicant has demonstrated significant action toward perfecting their appropriation when considering whether to grant a requested extensions. The workshop for this proposed regulation will take place on January 13, 2021 at 9:00 am.

R170-20

This draft regulation proposes additional definitions and requirements related to Professional Engineers, Professional Land Surveyors and appointed state Water Right Surveyors as well as proposed disciplinary actions against surveyors. The workshop for this regulation will take place on February 5, 2021 at 9:00 am.

The upcoming workshops are anticipated to be held virtually. The current deadline to provide public comment is through the date of the workshops.

If you would like to participate in the water related proposed regulations, please consider attending the workshops!

In a previous blog, we looked into who owns an aquifer: does it belong to private individuals or the public? Under the ad coelum doctrine, the surface owner holds the ground itself – rocks, dirt, and the like – as private property, owned all the way down to the Earth’s core. On the other hand, the public collectively owns water, taken for private use through the rule of capture, or the ferae naturae doctrine.[1] Because an aquifer is a “body of permeable rock which can contain or transmit groundwater,”[2] the rules related to aquifers are a complex combination of the two competing doctrines. In our previous update, we highlighted a California district court case, Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians v. Desert Water Agency, et al, that seeks an answer to the question of aquifer pore space ownership.[3]

The Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians (“Tribe”) sued the Coachella Valley Water District and Desert Water Authority (“Defendants”) to protect the aquifer under its reservation from groundwater depletion and water quality degradation. The Tribe argued that the pore spaces within the aquifer are its property under the ad coelum doctrine. The Defendants believe that the public owns pore spaces. The court has not yet addressed the question of whether the pore spaces are public or private property. However, the case has progressed since our last post and we are due for an update.

The Tribe and Defendants agreed to split the litigation into three phases when the Tribe first filed the case in 2013. Phase 1 was to decide whether the Tribe had a reserved right to groundwater in principle. Thereafter, Phase 2 would resolve if this reserved right contained a water quality component, the method of quantification of a reserved groundwater right, and if the Tribe owned pore spaces within the aquifer. Phase 3, if necessary, would quantify the Tribe’s reserved groundwater right and ownership of pore space.

In Phase 1, the court granted summary judgment to the Tribe on its groundwater right claim. The decision essentially declared without a trial that the Tribe did in fact have a reserved right to groundwater. Phase 2 was delayed while the Defendants unsuccessfully appealed to the 9th Circuit and then unsuccessfully sought Supreme Court review.

Like Phase 1, Phase 2 proceeded to summary judgment. The court ruled that the Tribe can seek a declaration that it has an ownership interest in sufficient pore space to store its groundwater. However, the Tribe did not argue that it owns the pore space as a “constituent element” of its land ownership in its initial complaint, and the court could not consider it. Recently, the Tribe submitted an amended complaint including its pore space as “constituent element” of land ownership argument, which is now before the court.

The question of whether the Tribe has ownership of the pore space beneath its reservation is the only item left for the court to decide in this phase; the answer could have a real impact on groundwater issues, as it may be one of the first cases to directly address the pore space question. Another controversy is bubbling over pore spaces in North Dakota, starting with the case Mosser v. Denbury Res., Inc., 2017 ND 169 (2017), passage of H.B. 2344, and legal challenges to the bill by the NW Landowners. Keep an eye on the blog for our next update on this case that could affect you!

This blog was drafted with the assistance of Drew Hancherick, a current law student attending Lewis and Clark Law School.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuius_est_solum,_eius_est_usque_ad_coelum_et_ad_inferos

[2] Oxford Online Dictionary, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/aquifer

[3] The case is presently before the United States District Court for the Central District of California, Docket No. ED CV 13-00883-JGB-SPX. Plaintiffs filed the complaint on May 14, 2013.

By Therese Ure and Lisa Mae Gage

Nevada Division of Water Resources (“NDWR”) submitted draft administrative regulation amendments to the Legislative Council Bureau for this regulation cycle (the proposed amendments can be found at http://water.nv.gov/documents/NDWR_Prop_Admin_Regs-Hearings_EOT_Water_Right_Surveyor_6-8-2020.pdf ). A public workshop concerning the administrative regulation amendments was hosted by NDWR on June 24, 2020 wherein NDWR received public comments during the workshop and subsequent written comments. Since the workshop NDWR has made revisions to the proposed regulation amendments based on the comments received.

In an effort to keep the public informed of its revised regulation amendment proposal, and in order to allow the public continued opportunity to provide comments, NDWR has advised that 1) it has created and is maintaining an email distribution list to provide communications concerning its ongoing revisions; 2) it is planning on holding at least three (3) additional public workshops prior to the beginning of the 2021 legislative session; 3) it will provide bi-monthly updates regarding the planned workshops; and 4) it does not intend to take the regulations to a public hearing until after the 2021 legislative session concludes.

To stay informed and up-to-date on these possible administrative regulation changes that may affect water right holders throughout the state of Nevada, we suggest signing up for updates via NDWR’s email distribution list. Instructions for subscribing to the notification list can be found by visiting http://water.nv.gov/documents/AdminRegs%20Listserv%20Instructions.pdf.

In case you missed it, on June 10, 2020, Schroeder Law Offices presented a webinar on stockwater on and off public land . Panelists included Laura Schroeder and Therese Ure of Schroeder Law Offices, P.C. and Alan Schroeder of Schroeder Law in Boise Idaho. The panelists discussed stockwater in Nevada, Idaho, and Oregon.

. Panelists included Laura Schroeder and Therese Ure of Schroeder Law Offices, P.C. and Alan Schroeder of Schroeder Law in Boise Idaho. The panelists discussed stockwater in Nevada, Idaho, and Oregon.

The webinar’s topics included:

Participants’ questions confirmed the relevance of stockwater on public land. Both Attorney’s Alan Schroeder and Laura Schroeder answered questions regarding the Limited Agency Agreement for the Purpose of Establishing and Maintaining Stockwater Rights Under the Laws of the State of Idaho. Many Bureau of Land Management permittees recently received these agreements. Panelists discussed the issue of federal stockwater ownership in Idaho throughout the webinar. Discussion included consideration of the pending Idaho stockwater legislation and the Idaho Supreme Court decision in Joyce Livestock Company v. United State of America.

Participants’ questions confirmed the relevance of stockwater on public land. Both Attorney’s Alan Schroeder and Laura Schroeder answered questions regarding the Limited Agency Agreement for the Purpose of Establishing and Maintaining Stockwater Rights Under the Laws of the State of Idaho. Many Bureau of Land Management permittees recently received these agreements. Panelists discussed the issue of federal stockwater ownership in Idaho throughout the webinar. Discussion included consideration of the pending Idaho stockwater legislation and the Idaho Supreme Court decision in Joyce Livestock Company v. United State of America.

To view the full webinar, please visit: https://www.water-law.com/webinars/stockwater-rights/

Schroeder Law Offices provided weekly webinars on an array of water related issues during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. To view any previous webinars, please visit: https://www.water-law.com/webinars/.

The Nevada Division of Water Resources (NDWR) proposes substantial changes to Nevada’s water right procedures. The agency first announced the proposed changes when it released a Small Business Impacts Survey on June 1, 2020. The survey invited participants to state if they believed the proposed regulation amendments would impact small businesses. NDWR followed the survey on June 8, 2020 with a Notice of Public Workshop. The notice invites interested citizens to attend and give general input on the proposed amendments.

of Water Resources (NDWR) proposes substantial changes to Nevada’s water right procedures. The agency first announced the proposed changes when it released a Small Business Impacts Survey on June 1, 2020. The survey invited participants to state if they believed the proposed regulation amendments would impact small businesses. NDWR followed the survey on June 8, 2020 with a Notice of Public Workshop. The notice invites interested citizens to attend and give general input on the proposed amendments.

NDWR is unique in Nevada. Unlike most Nevada agencies, NDWR is not bound by Nevada’s Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”). The APA governs how Nevada agencies must conduct rulemaking. Although NDWR is not strictly bound by the APA, it elects to follow APA rulemaking procedures.

Rulemaking under the Nevada APA is a seven-step process. The agency must:

Here, NDWR completed a small business impact review, drafted proposed regulations, and provided 15-day notice for its public workshop. The workshop will take place at 9 AM on June 24, 2020. Due to ongoing Covid-19 restrictions, the workshop will occur via telephone and skype. Information for joining the workshop can be found on the Notice of Public Workshop.

Interested citizens should also monitor http://water.nv.gov/ for the Notice of Intent to Adopt Regulations. NDWR has not issued this notice. However, a Notice of Intent to Adopt Regulations must include the date, time, place, and manner by which the public can submit comment. NDWR will provide 30 days after the notice for the public to provide comment. NDWR will also hear oral comments at the public hearing.

The regulations propose substantial changes to Nevada Administrative Code (“NAC”), Chapter 533. The chapter governs the administrative process for permitting and certificating water rights. You are highly encouraged to review the proposed changes here. However, some proposed changes to note include:

Public Participation

Public Participation Public participation is inherent in an agency’s rulemaking process. If these changes affect you, exercise your right to participate in the process by attending the June 24, 2020 workshop, submitting public comment pursuant to the Notice of Intent to Adopt Regulations, and attending the upcoming public hearing.

(Image Credit: https://www.bbklaw.com/news-events/insights/2018/authored-articles/12/public-comment-time-limit-ok-d-by-court,http://water.nv.gov/documents/AB%2062%20Informal%20Public%20Workshops.pdf )

By Therese Ure and Lisa Mae Gage

In case you missed it, on May 13, 2020, Schroeder Law Offices presented a very informative webinar regarding water right adjudications. (To view the full webinar, please visit https://www.water-law.com/webinars/water-right-adjudication/). During this webinar, attorneys Laura Schroeder and Therese Ure provided attendees with valuable information concerning water codes in Oregon and Nevada, the post code adjudication process, types of evidence considered in determining a pre-code vested right and general components of decrees.

One major take away from this webinar is the Sunset Date for Nevada vested claims. Pursuant to Nevada Senate Bill 270 that was enacted in 2017, Nevada now has a “Sunset Deadline” of December 31, 2027 by which all vested claims must be filed with Nevada Division of Water Resources (“NDWR”). While this deadline merely directs the date on which the Proof of Appropriation must be filed with NDWR, it is recommended that consideration be paid to researching the supporting historical information required to “Prove Up” the vested claim once the source is ripe for adjudication. For more tips on researching historical water use, please go to http://www.water-law.com/water-rights-articles/nevada-water-rights/.

Schroeder Law Offices has been providing weekly webinars for an array of water related issues during the COVID 19 pandemic. To review any previous webinars, or to sign up for any future webinars, please visit https://www.water-law.com/webinars/.

This webinar video discusses the ins and outs of water right research in Oregon. Tara Jackson presents, moderated by Sarah Liljefelt.

Tara Jackson is a veteran Senior Paralegal with Schroeder Law Offices in Portland. Tara has been on the front line in dozens of client matters. She has been the go-to expert in Oregon water right research for over 12 years.

Sarah Liljefelt is a shareholder and partner at Schroeder Law Offices. She manages the Portland office and is very familiar with Tara’s work.

In the video, Sarah and Tara take viewers through Oregon Water Resources Department’s (OWRD) website. The video begins at the OWRD website homepage to show viewers where to begin their research.

After the brief overview it gives step-by-step instructions on how to use the Water Right Information System (WRIS) to search for water rights and what you will find in a WRIS search. Second, the video explains the interactive water right mapping program. Third, there is an explanation of how to find documents in the Vault and information on water wells from the Well Report Query. And fourth, the video ends with a short explanation of how to find groundwater data using the Groundwater Information System (GWIS) mapping program and database.

This video will provide you with the basic tools to research water rights related to a particular property or find specific water right documents and much more.

You can view other related webinars here.

For the sixth COVID-19 webinar, paralegals Rachelq Harman, Tara Jackson, and Lisa Mae Gage will discuss the research tools and resources available on the Idaho Department of Water Resources (IDWR), Oregon Water Resources Department (OWRD), and Nevada Division of Water Resources (NDWR) online databases. The webinar will occur in 3 parts on May 20, 2020.

First, Rachelq, moderated by attorney Laura Schroeder, will present on IDWR’s online resources from 11:00 AM to 11:30 AM Pacific Time (12:00 PM to 12:30 Mountain Time). Next, Tara, moderated by attorney Sarah Liljefelt, will present on OWRD from 12:00 PM to 12:30 PM Pacific Time. Finally, Lisa Mae, moderated by attorney Therese Ure, will present on NDWR from 1:00 PM to 1:30 PM Pacific Time.

Click on the state’s name to register for the Idaho, Oregon, and/or Nevada webinars. We invite you to attend all three, or just the one(s) most relevant to you. If you have any issues with registration, please contact Scott Borison at: scott@water-law.com. If you can’t make it, stay tuned to our blog for announcements for information about the next webinars. Our previous webinars in the COVID-19 Series are available here.

Each of the May 20th webinars will offer suggestions on how to get the most out of each state’s online resources and water right information. First, we will provide an overview of what tools are available on each state’s website, then narrow our focus to water right look up and mapping tools. We will then take you through the steps needed to search for individual water rights. We will also explore the various online mapping tools and files available to aid in water right research.

We will offer a surprise discount for online research assistance to be provided by one of the experienced water rights paralegals who are panelists to this webinar for webinar participants.

The COVID-19 Webinar series will continue over next several weeks, including topics related to real estate due diligence and water management organization. Previous webinars are available on our website, giving you access to Schroeder Law Office’s educational events under the “social distancing” orders! Follow Schroeder Law Offices’ Water Law Blog for the most up to date information and announcements!

In the fourth COVID-19 webinar, Laura Schroeder and Wyatt Rolfe discussed how to conduct due diligence on water use rights. The webinar originally aired on May 6, 2020 from 12:00 PM to 1:00 PM. You can view the webinar here! Stay tuned to our blog for announcements for information about the next webinars. You can watch previous webinars in the series here.

In the fourth COVID-19 webinar, Laura Schroeder and Wyatt Rolfe discussed how to conduct due diligence on water use rights. The webinar originally aired on May 6, 2020 from 12:00 PM to 1:00 PM. You can view the webinar here! Stay tuned to our blog for announcements for information about the next webinars. You can watch previous webinars in the series here.

Learn the basics about water use rights in property transactions and determining if any issues are present. Receive practical information to locate any “red flags,” the most common issues encountered in water use right due diligence, including those related to small utilities. Topics will include:

The COVID-19 Webinar series continued over several weeks, including topics related to using the OWRD website to locate information and real property issues associated with water use rights. All webinars are available on our website, giving you access to Schroeder Law Office’s educational events under the “social distancing” orders! Follow Schroeder Law Offices’ Water Law Blog for the most up to date information and announcements!

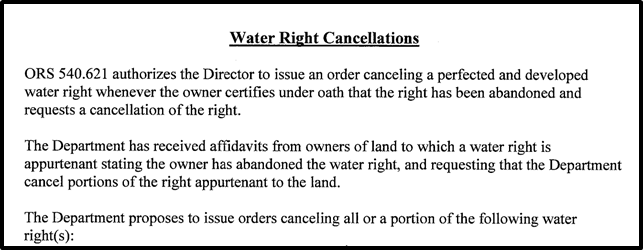

In the second COVID-19 webinar, Laura Schroeder and Sarah Liljefelt discussed what to do when you receive a notice of cancellation of your water right in Oregon. The webinar aired originally on April 22, 2020 from 12:00 PM to 1:00 PM. You can view the webinar here!. Stay tuned to our blog for announcements for information about the next webinars! You can view the other webinars in the series here.

Learn the basics about water rights cancellation, including the types of cancellation applicable to different water use rights, the steps in the process, and how to address or challenge the agency’s cancellation decision. Receive practical information to protect your water use rights, determine if water use rights are in good standing when purchasing new property, and conduct assessments of the water use rights on property you already own. Topics will include:

The COVID-19 Webinar series will continued in following several weeks, giving you access to Schroeder Law Office’s educational events under the “social distancing” orders! Later webinars will cover common water-related issues, including well construction issues, and illegal water uses. Follow Schroeder Law Offices’ Water Law Blog for the most up to date information and announcements!

As the first COVID-19 Webinar in new weekly series, Laura Schroeder and Therese Ure discussed the ins and outs of how watermasters regulate water in Oregon and Nevada. The webinar aired originally on April 15, 2020 from 12:00 PM to 1:00 PM. You can view the webinar here! Stay tuned to our blog for announcements and information for the next webinars! You can view other webinars in the series here.

Learn the nuts and bolts of how watermasters regulate water, issue shut off orders, and the rules watermasters must follow to distribute water. Receive practical tips to challenge a watermaster’s decision, potentially preventing enforcement until the decision is reviewed. Topics will include:

The COVID-19 Webinar series continued the following several weeks, giving you access to Schroeder Law Office’s educational events under the “social distancing” orders! Upcoming webinars will cover common water-related issues, including water use right cancellations, well construction issues, and illegal water uses. Follow our blog for the most up to date information and announcements!

Was your upcoming water law conference cancelled? Or are you itching to learn more about Oregon water law, but could never attend one of Schroeder Law Offices speaking events? Stuck inside due to Covid-19 orders? You’re in luck! Laura Schroeder will be offering a series of free webinars this spring covering a wide range of water law topics on our website.

The current schedule will include:

Further updates and instructions to attend will be coming soon. Stay tuned to our blog receive updates on these upcoming events and other water news!

National Ag Day is March 24, 2020. It’s a special day to recognize and celebrate the contributions of agriculture. We should all “thank a farmer” at every meal and every time we get dressed. Therefore, National Ag Day is an organized effort to do just that. See the Agriculture Council of America’s website for more details: https://www.agday.org/.

Especially today, the agricultural community is showing its every-day-grit. It does so by continuing its important calling of feeding and clothing the world in the face of the current COVID-19 outbreak. Today, children in rural families are home due to school closures. They are working alongside their parents to provide food and fiber for the other 99% of the population. Safety requires shutting down many industries to avoid spreading the virus. However, the agricultural and trucking sectors are working as hard as ever to ensure the rest of us have what we need to weather the storm. Planting, harvesting, milking, and calving do not stop in the face of a pandemic.

Oregon Governor Kate Brown issued an executive order on March 17th prohibiting gatherings over 25 people. Certain organizations (like farmers markets) didn’t know whether they would need to shut down operations as a result of the order. Consequently the Oregon Department of Agriculture issued guidance on March 20th. This guidance identified farmers, ranchers, food processors, farm workers, truckers, and service suppliers as “essential services” that are not required to shut down in response to the Governor’s order.

Schroeder Law Offices extends a giant “THANK YOU!” to the agriculture community. Agriculture is the backbone of the Nation on National Ag Day, during times of illness, and every day! It is truly our pleasure to provide water rights support to the agriculture community on National Ag Day and always.

Photo: The children of Bingham Beef in North Powder, Oregon, hearing “another job” during their extended “spring break.” Photo credit: Carly Carlson.