Corner Crossing Appeal

Appellate Court Rules on Corner Crossing Case

On March 18, 2025, the Tenth Circuit Appellate Court issued a ruling on Iron Bar Holdings v. Cape, et al., what has become commonly referred to as the “Corner Crossing Case”. As noted in our earlier blog, the Corner Crossing Case sets precedent on public land use in the West and settles a decades-long dispute between competing public land uses.

Background and District Court Outcome

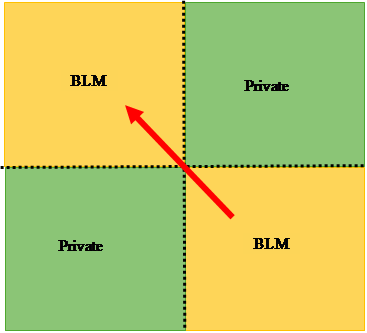

The case arose in the Federal District of Wyoming after several incidents in 2020 and 2021 involving four hunters pursuing deer and elk in southwest Wyoming. The hunters, including Brad Cape, Zach Smith, Phillip Yeomans, and John Slowensky were hunting BLM land checkerboarded with private land belonging to Iron Bar Holdings, the owner of a Wyoming based ranching operation. Due to prior disagreements with Iron Bar Holdings and hunters traversing from one BLM parcel to another via touching corners (i.e. “corner crossing”), Iron Bar Holdings posted and fenced the corners of its private land, to bar “corner crossing”. Iron Bar also deployed its staff to instruct corner crossers to leave and contact local law enforcement requesting they press criminal charges on any corner crossers. While law enforcement was called on the hunters involved in this case in 2020, no citations were issued. In 2021, the hunters returned and used a ladder with its bases placed on each BLM parcel to “corner cross”, climbing from one public block to another without touching Iron Bar Holdings’ private land.

According to the March 18, 2025, decision [1], Iron Bar Holdings sued the hunters in federal civil court for civil trespass, claiming $9 million in damages based on a possible 10-25% devaluation of its property due to loss of exclusive access to the elk-rich public land sections interspersed with its private land. The District Court judge ruled in favor of the hunters, finding that public land users who corner-cross are immune from civil liability as long as the crossers do not touch the surface of private land or damage private property. Iron Bar Holdings appealed the decision to the Federal Appellate Court for the Tenth Circuit.

Tenth Circuit Opinion

The Corner Crossing Case appeal was determined by a three-judge panel with a 3-0 decision. The sitting judges included Timothy Tymkovich, David Ebel, and Nancy Motriz. The appellate court’s 49-page decision upheld the District Court ruling and provided additional analysis on the legality of corner crossing. The decision contains a detailed and interesting history of the development of the public land survey system and federal land grants to railroad companies for the Transcontinental Railroad. Both are key elements giving rise to the present-day phenomenon of checkerboarded private and public land in the West.

Like in the District Court, the Unlawful Inclosure Act [2] of 1885 (“UIA”) was a primary factor in the Appellate Court’s decision affirming the District Court under de novo review. The UIA was passed “to prevent absorption and ownership of vast tracts of the public domain”, primarily by cattle barons. 43 U.S.C. § 1061 et seq. The Court acknowledged that the UIA was “designed to harmonize public access to the public domain with adjacent private land holdings.”

State Property Law Preempted by Federal Law

First, the Court briefly discussed state property law, including the ownership of airspace and the property owner’s right to exclude. In doing so the Court found the hunters corner-crossing was a trespass under Wyoming law. However, in applying the UIA, the Court also found that the state trespass law was preempted by federal law. In doing so, the Court reviewed over a hundred years of federal corner dispute cases spanning from 1885 to 1988.

Full Access to Public Lands

The Court concluded the UIA declares “[a]ll inclosures of any public lands. . .to be unlawful” including the “erection, construction, or control of any such inclosure” and the use of “force, threats, intimidation.” It also restricts prevention or obstruction of free passage or transit over or through the public lands. The court found this language expanded to all “inclosures of public land”, including non-physical barriers, such as Iron Bar Holdings “no trespassing” signs and its staff telling hunter to leave the public land.

The core principle of the UIA is that a landowner cannot maintain a barrier “which enclose public lands and prevents” access for a “lawful purpose.” U.S. ex rel. Bergen v. Lawrence, 848 F.2d 1502, 1511-1512 (10th Cir. 1988). However, the Court recognized a barrier itself is not a UIA violation, but it becomes one when its effect is to enclose. The Court further found that not every fence is a violation of the UIA as a fence can still permit adequate access such as via a gate. However, a fence that does prohibit access across federal land is a nuisance.

Conclusion

In sum, while the Tenth Circuit recognized that corner crossing may constitute civil trespass of a property owner’s airspace under state law, it found that such trespass is permissible if it is to overcome a UIA violation. As a result, the Court upheld the District Court holding that the hunters could corner-cross as long as they did not physically touch Iron Bar’s land.

Tenth Circuit holdings have binding precedent on the following states: Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. The ruling is also persuasive precedent for other States and appellate circuits in the West. It is unknown at this time if Iron Bar Holdings will petition the Supreme Court for certiorari (review). It must do so within 90 days of entry of the Tenth Circuit’s order.

[1] Our earlier blog says ~$7 million, which is consistent with the District Court decision. The appellate court decision says $9 million.

[2] Not a typo, that is the wording from the actual act.