The Oregon Water Resources Department (“OWRD”) does not use a single definition of an aquifer. Instead, it uses different applications of the word depending on the context. Scientifically, there is a generally accepted definition (which we discussed here: https://www.water-law.com/who-owns-an-aquifer/): “body of permeable rock which can contain or transmit groundwater.”[1] Depending on the location, context, and situation, OWRD and other state agencies might use a different definitions for “aquifer.” Each of these definitions have their own features, potentially leading to different interpretations.

OWRD’s General Definition

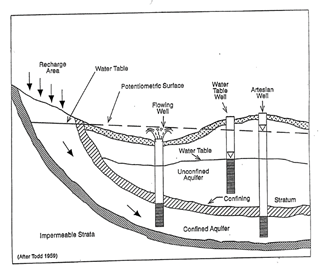

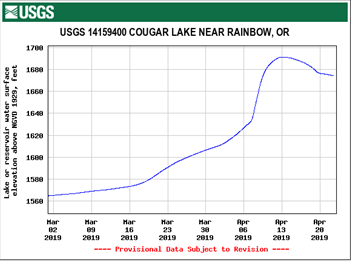

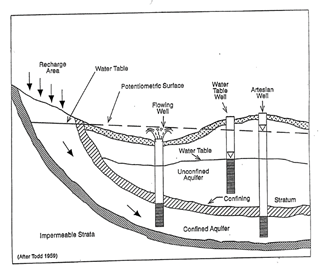

OWRD generally defines an aquifer under Oregon Administrative Regulation (“OAR”) 690-200-0050(9) as “a geologic formation, group of formations, or part of a formation that contains saturated and permeable material capable of transmitting water in sufficient quantity to supply wells or springs and that contains water that is similar throughout in characteristics such as potentiometric head, chemistry, and temperature (see Figure 200-2 [above]).” Potentiometric “head” is akin to the pressure of the water at a given location.

Compared to the scientific definition outlined above, OWRD restricts aquifers to those with similar potentiometric head, chemistry, and temperature. Aquifer characteristics can vary from location to location while still being within the same hydraulically connected system, called “anisotropic” or heterogeneous conditions. Permeability, water quality, and temperature can vary within an aquifer under the scientific definition above, but OWRD’s general definition does not allow for anisotropic conditions in a single aquifer.

“Aquifers” in the Upper Klamath Basin

Another definition of “aquifer” is located in the newly adopted rules in OAR Chapter 690, Division 25. These rules are restricted to the Upper Klamath Basin and supplant the Division 9 rules during 2019 and 2020 only. Under these rules, “groundwater reservoir” or “aquifer” is defined as “a body of groundwater having boundaries which may be ascertained or reasonably inferred that yields quantities of water to wells or surface water sufficient for appropriation under an existing right of record.” OAR 690-025-0020(4).

This definition merges the groundwater (the contents) with the aquifer (the container). Interestingly, this definition restricts the “aquifer” to areas that produce water “under an existing right of record.” This definition combines physical aspects, legal rights, and geographic components into a single non-scientific definition.

“Hydraulic Connection” under Divisions 9 & 25

Oregon Revised Statute Chapter 690 Division 9 regulates conjunctive management of surface water and groundwater throughout the State. The regulations prescribe when new groundwater appropriations may be allowed, and when existing groundwater use rights must be regulated off in times of shortage when a senior surface water call is made. The Division 25 rules supplant the portion of Division 9 for the Upper Klamath Basin related to regulation of existing groundwater use rights.

Under the Division 9 regulations, “hydraulic connection” means “water can move between a surface water source and an adjacent aquifer.” Under the Division 25 rules specific to the Upper Klamath Basin, however, “hydraulically connected” means “water can move between or among groundwater reservoirs and surface water.” Further, OWRD applies these differing definitions exactly the same, regulating down to deep, confined aquifers under Division 9 that are not “adjacent” to the surface water source, much as one would imagine OWRD doing under the more broad Division 25 definition that talks about water movement between various groundwater reservoirs.

Well Construction & Commingling Rules

Another version of “aquifer” is found in OWRD’s well construction rules. OAR 690-200-0050(9) defines “aquifer” as a “geologic formation, group of formations, or part of a formation that contains saturated and permeable material capable of transmitting water in sufficient quantity to supply wells or springs and that contains water that is similar throughout in characteristics such as potentiometric head, chemistry, and temperature.”

Under OAR 690-200-0043, a water supply well cannot be “constructed in a manner that allows commingling or leakage of groundwater by gravity flow or artesian pressure from one aquifer to another.” OWRD interprets its rules to prohibit comingling of groundwater between aquifers even when no water is currently present at the location of an alleged aquifer. Such is the case when a well is deepened due to the original water bearing zone no longer producing water. OAR 690-215-0045(4) prohibits the deepening of a well in such a way that will “result in commingling of aquifers.” OWRD interprets this rule to require sealing off the now-dry layers from the deeper water-bearing layers. Here, OWRD’s interpretation of an aquifer addresses the potential for commingling of groundwater, not actual commingling. In this case, the term “aquifer” refers to groundwater potentially, but not actually, present in a former water-bearing zone.

When a well is constructed, the well driller submits a report called a “well log” to OWRD. These logs show the various types of soils and water bearing layers found during the course of the drilling. OWRD does not require well drillers to be certified geologists, so these descriptions are often informal and not scientifically reviewed. Well logs typically do not include potentiometric head, chemistry, or temperature information for each water-bearing zone encountered in a well. Thus, whether a water-bearing zone constitutes a distinct aquifer is a challenging question when only reviewing a well log without the scientific information required in the definition above.

OWRD does not typically review well logs unless an issue arises. A bill introduced in this legislative session, H.B. 2331 A (2019), would have required OWRD to review well logs when received by the agency: https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2019R1/Measures/Overview/HB2331. However, this bill remained in committee and was not adopted. Therefore, OWRD continues at the present time to review well logs inconsistently and sometimes not until decades after well completion, and it can sometimes be challenging for drillers to identify separate aquifers for the purpose of meeting well drilling standards due to OWRD’s differing and numerous aquifer definitions.

DEQ Rules

To compare with OWRD, the Department of Environmental Quality’s (“DEQ’s”) rules, defines aquifer as “an underground zone holding water that is capable of yielding a significant amount of water to a well or spring.” OAR 340-044-0005(2). This definition is the most similar to the scientific definition above, without the restriction to a certain characteristic (like water quality) or legal status (like status of water rights or ascertainable boundary).

Conclusion

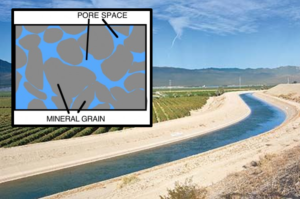

The definitions for “aquifer” used by OWRD and DEQ deviate from the generally accepted scientific definition. Under the scientific definition, the permeable rocks define the extent of the aquifer (even if no water is present at the time). Under both OWRD and DEQ definitions, the water-filled-portion of the aquifer determines its extent, rather than the permeable rock “container” for the groundwater. Further, OWRD’s definitions add other characteristics, like potentiometric pressure, chemical, temperature, ability to determine a boundary, location in proximity to surface water, or legal right to the basic scientific term, though it is questionable whether OWRD gives due regard to these additional elements, and OWRD usually regulates groundwater in the most restrictive manner regardless of the applicable definitions in each context. As groundwater management controversies continue, the differences between these definitions may (and should) come under additional scrutiny.

Make sure to stay tuned to Schroeder Law Offices’ Water Blog for more news that may affect you!

[1] Oxford Online Dictionary, https://www.lexico.com/definition/aquifer